Phoenicians in America

05 Mar 2021The theory of Phoenician discovery of America suggests that the earliest Old World contact with the Americas was not with Columbus or even Norse settlers, but with the Phoenicians (or, alternatively, other Semitic peoples).

There’s no wonder that there are so many controversies surrounding these enigmatic people which we still know little about, ranging from the extent of their sea travels to their religion and alleged child sacrifices. Ironically, although their alphabet became one of the most widely used writing systems in the West, very few Phoenician manuscripts have survived in the original or in translation due either to their destruction during Macedonian and Roman aggression or for having been written on easily perishable material like papyrus.

People generally consider this particular theory to be fringe because quite a few artifacts speaking in its favor are now considered to be forgeries. However, there are still people who vehemently support it and there’s much more evidence and controversy than one might think.

Archaeological evidence

The Paraíba Inscription

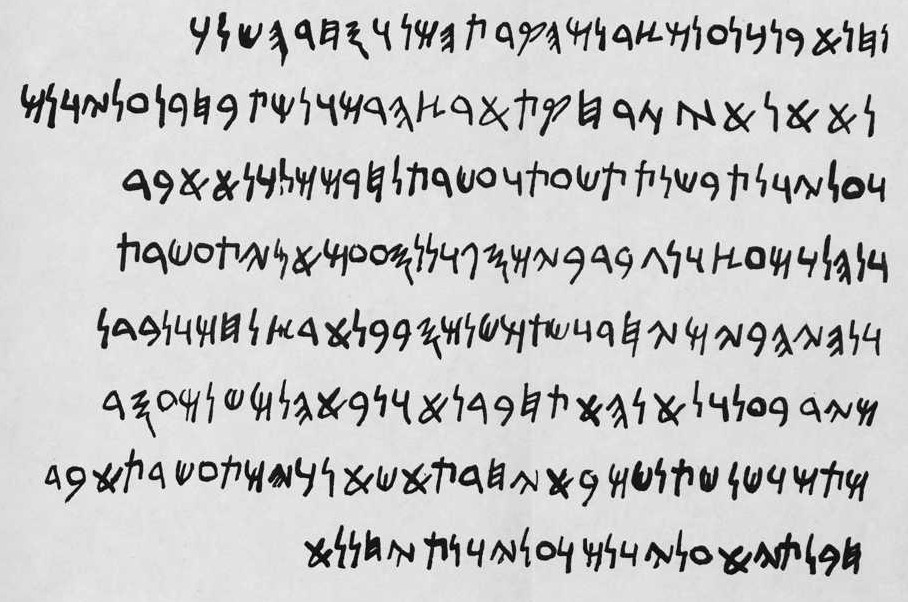

In 1872, the National Museum of Brazil received a letter signed by a man named Joaquim Alves da Costa, which contained a transcription of the inscriptions found on a stone at “Pouso-Alto on the shores of the Parahyba”.

The director of the museum Ladislau de Souza Mello Netto first accepted the inscription as genuine, but by 1873, philologist Ernest Renan convinced him that it was a forgery. According to his translation, the inscription tells the story of “Sidonian Canaanites”, who set sail around Africa and wound up on the shores of Brazil during the nineteenth year of the reign of King Hiram, some 500 years BC.1

Inscriptions sent along with the letter.

Inscriptions sent along with the letter.

- We are children of Canaan from Sidon from the Eastern kingdom of merchants and are cast,

- I pray now, where there is (?gold amids a/a far off?) land of mountains and offered a chosen one to the Most High gods

- And Goddesses in year 19 of Hiram’s reign, I pray (still) strong

- from the valley of Ezion-geber at the Red Sea there by journeyed with 10 ships

- we were at sea together assuredly two years around the land of Ham separated

- by the hand of Baal and no (longer) remained among our companions, now we have come here 12

- men and three women at this land devoted I make, even whom men of wealth bow the knee,

- a pledge to the Most High Gods and Goddesses (with) sure hope.

Netto also reports that all efforts of locating the original author of the inscription were in vain, which led him to believe that it was a hoax.

Side-note: The skeptical website BadArcheology.com claims that there was a real person Joachim Alves da Costa Freitas, who lived close to Pouso Alto in Minas Gerais province during the 1870s. Sadly, the link seemingly proving this leads to now-defunct Yahoo Groups and it doesn’t seem to be archived anywhere. If you know how to verify such information in some official records, please let us know!

The hypothesis was brought up again in 1967 by Cyrus Herzel Gordon, an expert in Semitic languages and head of the Department of Mediterranean Studies at Brandeis University, well-known for his translations of the ancient Cretan “Linear A”. He provided a slightly different translation and concluded that “it is obvious that the text is genuine since it didn’t copy any Semitic writing that would have been widely accessible at the time.”2

Another contemporary expert on Semitic languages, Frank Moore Cross, disagreed, supporting Renan’s opinion that the letterforms cover a range of ten centuries and that they could be made with knowledge of that time (see e.g. Jordan Moabite Stone from 18703).

Here is Dr. Gordon’s translation (or rather, interpretation) of the text:

We are Sidonian Canaanites from the city of the Mercantile King. We were cast up on this distant shore, a land of mountains. We sacrificed a youth to the celestial gods and goddesses in the nineteenth year of our mighty King Hiram and embarked from Ezion-geber into the Red Sea. We voyaged with ten ships and were at sea together for two years around Ham [Africa]. Then we were separated by the hand of Baal and were no longer with our companions. So we have come here, twelve men and three women, into New Shore. Am I, the Admiral, a man who would flee? Nay! May the celestial gods and goddesses favour us well!

Let’s conclude with a wonderful summary from Austin Whittall’s Patagonian Monsters blog: “So, we have a letter with a transcription of inscriptions found on a stone, that was never actually seen by scientists, it was posted from an unknown place on an ambiguous river by a person who could not be found later. Its text was, according to some scholars badly written and therefore a hoax, but, according to others, genuine.”4 Make of that what you will.

Bat Creek inscription

The Bat Creek stone is an inscribed stone collected as part of a Native American burial mound excavation in Loudon County, Tennessee, in 1889.

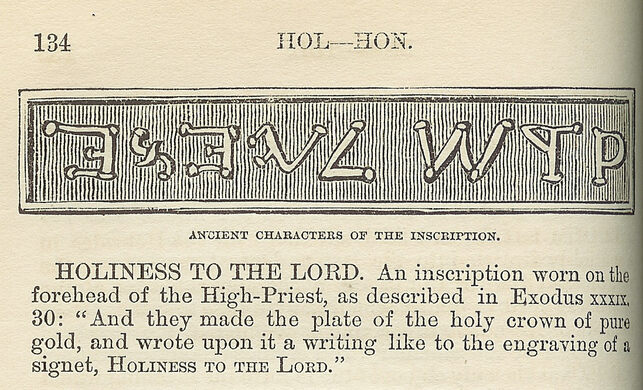

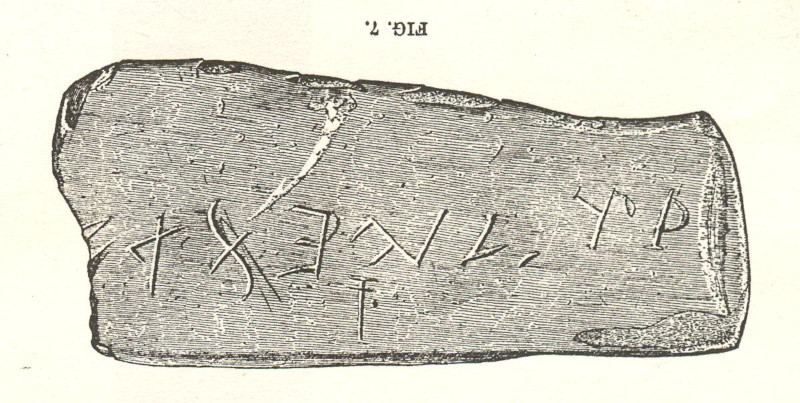

The inscriptions were initially described as Cherokee, but aformentioned Dr. Gordon correctly identified them as Hebrew.

However, in 2004, Robert C. Mainfort and Mary L. Kwas noticed the glaring similarities with an inscription that was circulating in a Freemason book, indicating that the stone is a religiously-motivated nineteenth-century forgery.5 The inscription in question, an 1860s artist’s impression of how the Biblical phrase QDSh LYHWH, or “Holy to Yahweh,” would have looked in Paleo-Hebrew letters, is reproduced below along with the Bat Creek stone:

|

|

| General History, Cyclopedia, and Dictionary of Freemasonry, 1870 | Bat Creek Stone inscription, found in 1889 |

Los Lunas Decalogue Stone

This inscribed stone is located on a 400-foot high mesa in Hidden Mountain, near Los Lunas, New Mexico. It is written in Paleo-Hebrew using the north Canaanite script of the early first millennium BC and it appears to be a version of Ten Commandments.

Since the stone’s discovery in the 1930s, several different translations were proposed. But it was a translation of Robert Pfeiffer of Harvard’s Semitic Museum from 1949 that created the greatest interest among scholars and others.

Many ascribe the first mention of the stone in print to the late Prof. Frank C. Hibben, an archaeologist from the University of Mexico, in 1933, though no record exists of his having published anything on the subject. It was first reported by Prof. James D. Tabor of the Dept. of Religious Studies, University of North Carolina - Charlotte, who interviewed Hibben in 1996.6

Hibben reports that he first saw the text in 1933. At the time it was covered with lichen and patination and was hardly visible. He was taken to the site by a guide who had seen it as a boy, back in the 1880s.” Hibben’s assessment of its age in the 1930s, based on the growth of mosses and lichens on it, was that the incised characters were at least a hundred years old.

The stone is blanched (from being cleaned by Boy Scouts in the 1950s, Hibben told Tabor), making dating through the patina, the surface layer of the rock, impossible. The first line has been scratched out by a vandal in 2006, but the rest of the inscription is completely legible.

David Atlee Phillips, curator of Archeology at the Maxwell Museum of Anthropology and professor of anthropology at the University of New Mexico, finds it much more likely that the inscription is the work of con-artists instead of the evidence of an ancient civilization. The smoking gun for Phillips is the usage of the “caret”, the upside-down V symbol placed under a piece of text where something has been missed out. Though sometimes found in ancient Latin and Greek texts, it is not known in Hebrew until the Middle Ages. To make matters worse, it is above a dot that seems to be a full stop (or period); full stops did not exist in ancient Hebrew. Moreover, there are Greek letters of a slightly later date mixed in with Hebrew forms. [citation needed]

In any case, even before 1880, and certainly before 1933 when Hibben first described the stone, enough had been learned about Paleo-Hebrew to account for a contemporary forgery. See e.g. A Discourse Concerning Sanchoniathon’s Phoenician History by Henry Dodwell from 1691.

Also, let’s not discount the presence of Jewish refugees in the earliest waves of Spanish colonists and settlers in the 16th or 17th century in today’s New Mexico - one of the farthest outposts in the empire of New Spain. It was an excellent place to avoid the horrors of the Inquisition.

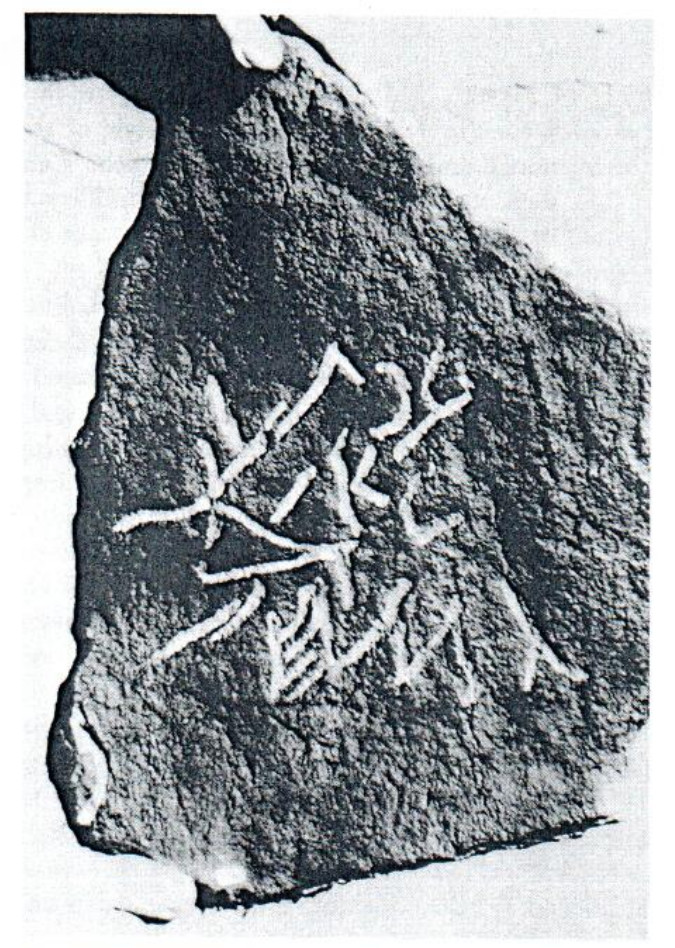

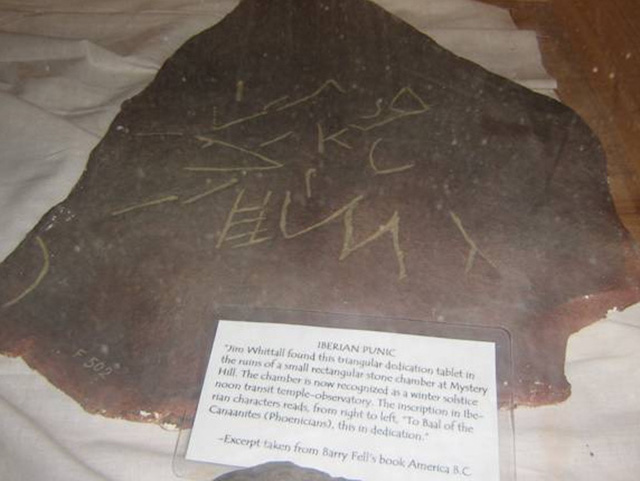

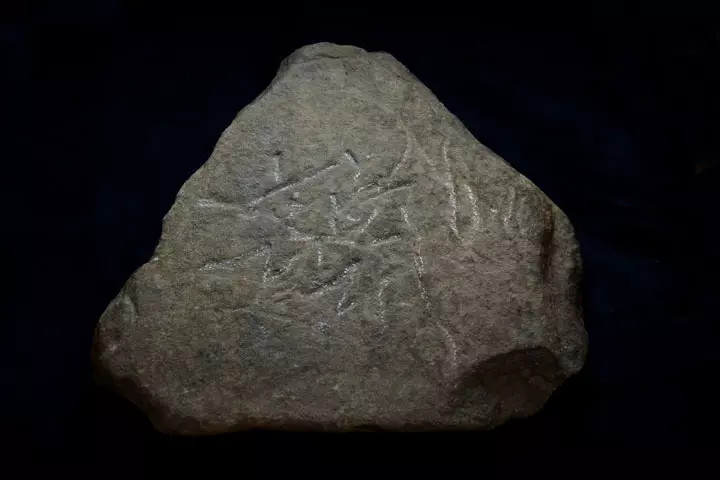

Baal Stone

The triangular stone, first documented by archaeologist James P. Whittall II, was popularized in the book America B.C. by Barry Fell. According to Fell, the inscription is in the Iberian Punic script and says “To Baal of the Canaanites, this in Dedication”.7

It was found on a site called America’s Stonehenge in Salem, New Hampshire, previously called Mystery Hill by its owner William Goodwin who believed it was built by Culdee monks from Ireland. The place was later sold to Bob Stone whose son still owns the site and the stone.

Side-note: One of the photos circulating the internet which apparently shows the artifact is definitely a replica. Although the inscriptions are more or less equal to the ones depicted in Fell’s book, it’s clearly a different stone.

|

|

Another claim was presented (relatively) recently at the History Channel TV show America Unearthed by Scott Wolter and a son of the current owner of the site. They hint at the possibility of the Phoenician link with the site by showing that the summer solstice sunrise alignment of American’s Stonehenge can be extended all the way to the Stonehenge and continues straight into the city of Beirut, Lebanon.8

Apart from referring to Lebanon as “the ancient home of the ancient Phoenicians”, they don’t explain what’s the connection with England’s Stonehenge. They also fail to mention that while the place we call Beirut today was most likely settled, it doesn’t seem to play any big role in historical records compared to cities like Byblos or Sidon.

Admittedly, the summer solstice sunrise alignment of America’s Stonehenge does point roughly in the direction of Stonehenge but remember that the exact course of this line is obviously very sensitive on the initial degree. Lines that start more or less parallel can diverge by several kilometers by the time they reach England.

Another side-note: Just a few days before finishing this article, a QAnon supporter allegedly vandalized the megalithic monument with the infamous WWG1WGA slogan and his Twitter handle.9

Plymouth State University archaeologist David Starbuck notes the 19th-century quarrying marks on many of the stones and said that the site has been altered so many times over the decades—particularly by the early owner William Goodwin starting in 1936—that there will never be a way to settle the argument over its authenticity.10

Sherbrooke stones

According to a 1975 newspaper article, A Laval University’s Prof. Thomas Lee found three stones in Eastern Townships near Quebec which could indicate that North America was visited by North Africans 500 years before the birth of Christ.

Prof. Thomas Lee said the stones were discovered “sometime early in this century” but the Egyptian inscriptions were written in a Libyan script not deciphered until last year. He said the earliest mention of the stones he has seen is in a letter dated Dec. 26, 1910, but he “got the impression the stones were not in the museum at that time.” A spokesman for the museum said it has had the stones since at least 1910.11

He said one stone is inscribed: “Expedition that crossed in the service of Lord Hiram to conquer territory.” The other of the pair discovered together bears the inscription: “Record by Hata, who attained this limit on the river, moored his ship and engraved this rock.” The stone which was found alone reads: “Hanno, son of Tamu, reached this mountain landmark.”,11 Probably alluding to the famous Hanno the Navigator himself.

See also: Dighton Rock

Coins

Roman coins

Reports of Roman coins in America go back to the 16th century. The earliest account is that of Marineo Siculo, who reported in 1533 that a coin bearing the image of Augustus was found in the gold mines of Panama.12 In the 19th century, two more finds were reported to be found at two different but neighboring locations in Tennessee. William C. Atwater was the first to discuss this material in 1818 but remained very skeptical.13 His contemporary Haywood, a proponent of the idea that Romans, Hebrews, etc. played a role in forming Native American culture, was not so skeptical; he published a list of objects suggestive of transoceanic contact, including 4 Roman coins all discovered around a town in Arkansas.14 The first mention of a Hebrew coin is from a letter sent to editors of The New York Times in 1860.15

1970s Phoenician coins

In the 20th century, discoveries started to mount up rapidly. Starting in 1913, when a Macedonian tetradrachma was found while digging a house foundation in Montana. The first mention of a coin suggesting direct Phoenician contact comes from the non-peer-reviewed (and now defunct) Anthropological Journal of Canada in a paper by Joseph B. Mahan and Douglas C. Braithwaite in 1975. They describe the discovery of a “Syracusan coin” by a boy in Phenix City, Alabama, who wanted to trade it for candy. He said he found it near his home at the edge of the city.16

The coin was later sent to Preston E. Blackwell, from the University of Georgia, who sent it to the Fogg Museum in Boston for identification. Museum officials identified the coin as a Syracuse coin dating from 490 BC. According to the Blackwell, the coin was later stolen from his wallet when he was hospitalized.16

The next publication to discuss the coins was a 1977 cover story by Norman Totten titled Carthaginian coins found in Arkansas and Alabama. Totten had been sent a coin similar to the one described by Mahan and Braithwaite by professor Barry Fell. Totten concluded that the coin was genuine and that based “on the obverse style alone, one might date this coin to about 350” BC. Fell got the coin from an amateur archaeologist Gloria Farley from Eastern Oklahoma Historical Society, who in turn got it from a man who claimed he found it with a metal detector buried six inches deep in a field near Cauthron, Arkansas. 17

Mark A. McMenamin from Mount Holyoke College, a previous proponent of their authenticity, provided exhaustive recapitulation of all evidence “Fell’s” coins and concluded that all of these were most likely modern forgeries.18

Finding patterns

Up to date, some 40 out-of-place coins are documented in the scientific literature (most of them being Roman coins). The striking increase in coin discoveries comes after WWII, most of them are reported in the 60s and 70s.

An interesting aspect is that the dates minted on coins are spread across much of Greek and Roman history ranging from 490 BC to 800 AD, which would imply prolonged contact for hundreds of years if we would accept all evidence as authentic.

For this reason, Jeremiah F. Epstein from the University of Chicago, who provided an exhaustive assessment of all evidence available in the 1980s, concludes:

The significance of the occasional discovery of a Roman, Greek or Hebrew coin in America is hard to asses, largely because such discoveries are comparatively rare and seldom adequately documented.

When one examines the dates of the coin discoveries, the distribution of the finds, and the times when the coins were minted, the most plausible interpretation is that the coins were lost recently. In fact, most of them appear to have been lost since WWII.

The biggest stumbling block in the way of giving these coins pre-Columbian status is that none have been found in documented prehistoric contexts.19

But what about those 15th to 19th-century finds?

The long period of time between the first report, in 1533, and the, in 1818, should arouse suspicion. If they were valid, one would imagine that ancient coins would have shown up in increasing numbers as America became settled.19

That however didn’t happen until after the last world war.

Historical evidence

Ptolemy’s Geography

In 2013, Lucio Russo has speculated about a probable arrival of Phoenicians in the Americas in his philological analyses regarding the Fortunate Isles, a.k.a. Islands of the Blessed. This mythical winterless paradise from Greek mythology would deserve their own analysis, but for the sake of Russo’s argument, we will only look at Ptolemy’s Geography, which provides information about geographical longitude.

In his book, Ptolemy gives the coordinates of the Fortunate Isles but at the same time, he shrinks the size of the world by one-third compared to the size measured by Eratosthenes. He argues that the underestimate of the size is caused by incorrect identification of Fortunate Isles with the Caribbean, and therefore by attributing those same coordinates to the Antilles the world gets back to the right size, and also various other puzzling deformations in Ptolemy’s world map start to disappear.20

Russo also argues that the Antilles coordinates must have been known to Ptolemy’s source, Hipparchus. Hipparchus lived in Rhodes and may have gotten this information from Phoenicians sailors since they had full control of the western Mediterranean in those times.21

Diodoros of Sicily

Diodoros’ Library of History is remarkable for many reasons. This 40-volume book (of which only 15 books survive intact) is considered one of the earliest attempts at Universal history and also it is notably more detached from ‘Hellenocentric’ world-view22. It’s also a major source of our knowledge about Alexander the Great!

That being said, some passages are a bit controversial. For fans of Alternative History, he’s mainly notable for his mentions of Atlanteans (completely unrelated to Plato’s Atlantis), but it also contains this peculiar passage story about Phoenicians:

But now that we have discussed what relates to the islands which lie within the Pillars of Hercules, we shall give an account of those which are in the ocean. For there lies out in the deep off Libya an island of considerable size, and situated as it is in the ocean it is distant from Libya a voyage of a number of days to the west. Its land is fruitful, much of it being mountainous and not a little being a level plain of surpassing beauty. Through it flow navigable rivers which are used for irrigation, and the island contains many parks planted with trees of every variety and gardens in great multitudes which are traversed by streams of sweet water;

on it also are private villas of costly construction, and throughout the gardens banqueting houses have been constructed in a setting of flowers, and in them the inhabitants pass their time during the summer season, since the land supplies in abundance everything which contributes to enjoyment and luxury. […] the climate of this island is so altogether mild that it produces in abundance the fruits of the trees and the other seasonal fruits for the larger part of the year, so that it would appear that the island, because of its exceptional felicity, were a dwelling-place of a race of gods and not of men.(V-19)23

In ancient times this island remained undiscovered because of its distance from the entire inhabited world j but it was discovered at a later period for the following reason. The Phoenicians, who from ancient times on made voyages continually for purposes of trade, planted many colonies throughout Libya and not a few as well in the western parts of Europe. And since their ventures turned out according to their expectations, they amassed great wealth and essayed to voyage beyond the Pillars of Heracles into the sea which men call the ocean.

[…] The Phoenicians, then, while exploring the coast outside the Pillars for the reasons we have stated and while sailing along the shore of Libya, were driven by strong winds a great distance out into the ocean. And after being storm-tossed for many days they were carried ashore on the island we mentioned above, and when they had observed its felicity and nature they caused it to be known to all men.(V-20)23

Later, we are told that Tyrrhenians wanted to make a colony there, but Carthaginians prevented it:

[…] partly out of concern lest many inhabitants of Carthage should remove there because of the excellence of the island, and partly in order to have ready in it a place in which to seek refuge against an incalculable turn of fortune, in case some total disaster should overtake Carthage. For it was their thought that, since they were masters of the sea, they would thus be able to move, households and all, to an island which was unknown to their conquerors.

Could this be another reference to Fortunate Islands? And would that mean Canary Islands, Azores, or Americas?

Sources

-

Netto, Ladislau. Lettre a Monsieur Ernest Renan a propos de l’inscrioption Phenicienne apocryphe soumise en 1872 a l’Institut historique, geographique et ethnograpicque du Bresil, 1885 (ufrj.br) ↩

-

Gordon, Cyrus H. The Canaanite Text from Brazil, 1968 (jstor.org) ↩

-

Phoenicians in the Americas - Is the Paraiba Stone of Brazil Genuine? (boloji.com) ↩

-

Whittall, Austin. The “Phoenician” inscriptions from Paraiba, Brazil, 2011 (blogspot.com) ↩

-

Kwas, Mary L., Mainfort, Robert C. The Bat Creek Stone Revisited, American Antiquity, v. 69, n. 4, 2004. ↩

-

Tabor, James D. An Ancient Hebrew Inscription in New Mexico (archive.org) ↩

-

Fell, Barry. America B.C., 1978 (archive.org) ↩

-

America Unearthed TV Show, Season 01, Episode 06 - Stonehenge in America, 2012 ↩

-

Man arrested for allegedly carving QAnon slogan at ‘America’s Stonehenge’ (theguardian.com) ↩

-

Starbuck, David R. The Archaeology of New Hampshire: Exploring 10,000 Years in the Granite State, 2006 ↩

-

Lee, Thomas. Africans Visited North America 2,500 Years Ago - Archeologist, Winnipeg Free Press, 1976 (uhem-mesut.com, archived) ↩ ↩2

-

Siculo, Marineo. De las cosas memorables de España, 1530 (bizkaia.eus) ↩

-

Atwater, Caleb. Archæologia americana: transactions and collections of the American Antiquarian Society, p. 19, 1820 (loc.gov) ↩

-

Haywood, John. The Natural and Aboriginal History of Tennessee, p. 174, 1823 (archive.org) ↩

-

Schoolcraft, Henry R. The “Hebrew stone” in Ohio.; Letter from Mr. Henry R. Schoolcraft, sent to *The New York Times in 1860 (nytimes.com) ↩

-

Mahan, J., Braithwaite, D. Discovery of Ancient Coins in the United States, Anthropological Journal of Canada, v. 12, n. 2, p. 15-18, 1975 ↩ ↩2

-

Totten, Norman. Carthaginian Coins found in Arkansas and Alabama, ESOP IV, v. 88, 1977 ↩

-

McMenamin, Mark A. Phoenicians, Fakes and Barry Fell: Solving the Mystery of Carthaginian Coins Found in America, 2000 ↩

-

Epstein, Jeremiah F. Pre-Columbian Old World Coins in America: An Examination of the Evidence, 1980 (uchicago.edu) ↩ ↩2

-

Russo, Lucio. Far-reaching Hellenistic geographical knowledge hidden in Ptolemy’s data, Mathematics and Mechanics of Complex System, v. 6, n. 3, 2018 (msp.org) ↩

-

Russo, Lucio. L’ America dimenticata. I rapporti tra le civiltà e un errore di Tolomeo, 2013 ↩

-

Usher, Stephen. The Historians of Greece and Rome, 1970 (archive.org) ↩

-

Diodoros of Sicily. Library of History, 1st-century BC, English translation, 1933 (archive.org) ↩ ↩2