Dighton Rock

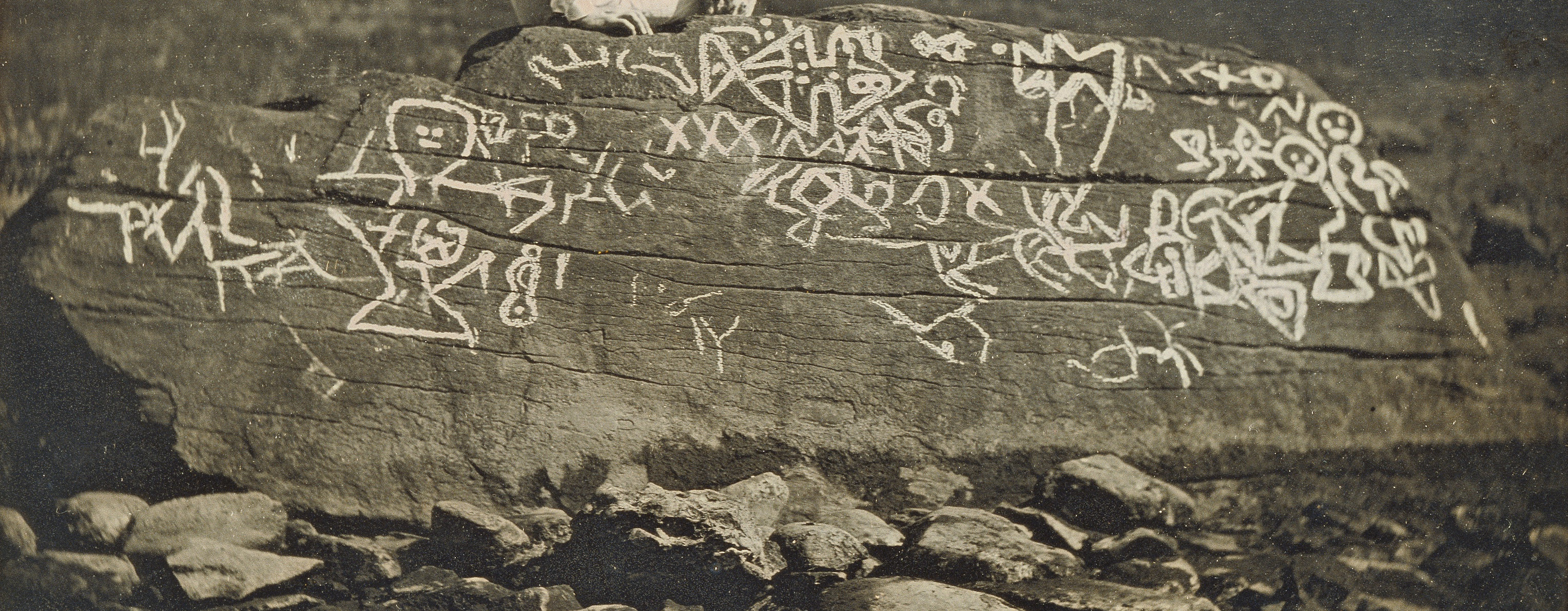

05 Mar 2021 Crop from Seth Eastman at Dighton Rock by Horatio B. King, 1853. Petroglyphs are traced with chalk.

Crop from Seth Eastman at Dighton Rock by Horatio B. King, 1853. Petroglyphs are traced with chalk.

The first reference to the carvings on the Dighton Rock dates back to 1680, when recent Harvard graduate John Danforth spotted the rock in what was then the town of Dighton and made a drawing of its carvings.1

The Dighton Rock, crystaline sandstone boulder found in the riverbed of the Taunton River in current Berkley, Massachsetts, bears petroglyphs which are still controversial to this day.

This artefact is remarkable mainly for how long it is has been generating range of very diverse speculations.

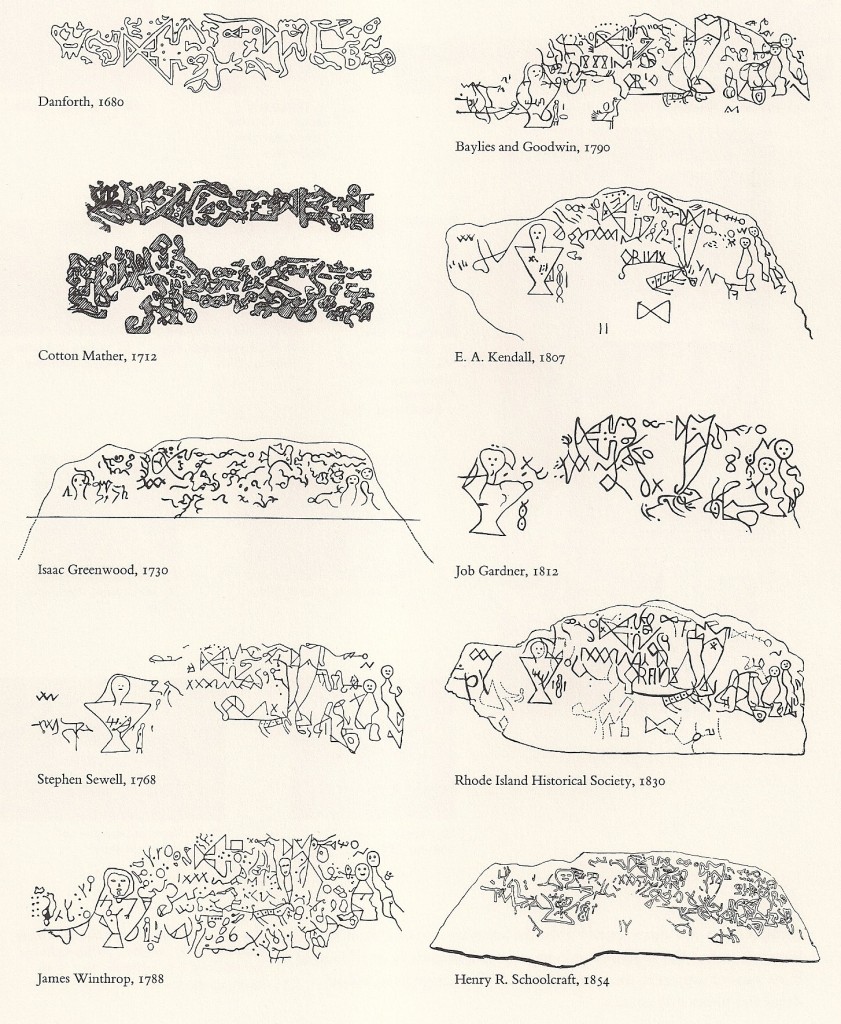

A compilation of transcriptions from Envisioning Information by Edward Tufte, based on Annual report of the Bureau of Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution 1880

A compilation of transcriptions from Envisioning Information by Edward Tufte, based on Annual report of the Bureau of Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution 1880

A book The Wonderful Works of God Commemorated by Cotton Mather from 1690 makes a reference to the rock:

Among the other Curiosities of New-England, one is that of a mighty Rock, on a perpendicular side whereof by a River, which at High Tide covers part of it, there are very deeply Engraved, no man alive knows How or When about half a score Lines, near Ten Foot Long, and a foot and half broad, filled with strange Characters: which would suggest as odd Thoughts about them that were here before us, as there are odd Shapes in that Elaborate Monument.2

Unfortunately, because no organic pigment or no other related artefacts have been found in the area, there’s no way of scientifically dating when the inscriptions were made. But there don’t seem to be any doubts about it’s antiquity.

Theories of origin

Despite a few hundred years of speculation, the extensive petroglyphs on the rock have still raise controversy. The most likely hypotheses attribute them to Native Americans. However, it was attributed also to Norse Vikings, Portuguese, Phoenicians, Chinese and more.

Side-note: Although not very relevant to the scholarly discussion, George Washington opined - while touring New England in 1789 - that the Dighton markings were left by American Indians. They were similar, he concluded, to Native American drawings he was familiar with in Virginia.[citation needed]

In 1767, Ezra Stiles, then president of Yale University, declared in his Election Sermon that the figures on the rock were of Phoenician origin. Stiles writes that a copy of inscription was sent to M. Gebelin of the Parisian academy of sciences, who comparing them with the Punic paleography, judges them punic, and has interpreted them as denoting, that the ancient Carthaginians once visited these distant regions.3

The controversy was reignited when Danish writer Charles Christian Rafn published his Antiquities Americanae in 1837, which contained more than 40 pages of analysis of the Dighton Rock. Rafn concluded the markings on the rock were Norse. His translation says:

Thorfinn and his 151 companions took possession of this land.4

In 1912, Edmund B. Delabarre announced his discovery of date “1511” and the name of “Miguel Corte-Real,” a Portuguese explorer who had left Portugal in 1502 and never returned. Fifty years after, Manuel Da Silva made a study of the rock and came upon two other clues, the Portuguese royal coat-of-arms and the Portuguese Cross of the Order of Christ. He published his findings in his Portuguese Pilgrims and Dighton Rock in 1971. Delabarre proposed that he had been heard from, in the inscription on the rock that read:

“I, Miguel Cortereal, 1511. In this place, by the will of God, I became a chief of the Indians.”[^delabbarre]

One of the most recent proposals came in 2002. This time, Gavin Menzies, in his book 1421: The Year China Discovered America, proposed that the inscriptions we made by Chinese explorers who had arrived and claimed the Americas for themselves at that time.5

Modern perspective

Sources

-

Annual report of the Bureau of Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, 1880 (archive.org) ↩

-

The wonderful works of God Commemorated, Cotton Mather, 1690 (umich.edu) ↩

-

Election Sermon, Ezra Stiles, 1783 (unl.edu) ↩

-

1421: The Year China Discovered America, Gavin Menzies, 2002 ↩